Husserl

“To begin with, we put the proposition: pure phenomenology is the science of pure consciousness.”

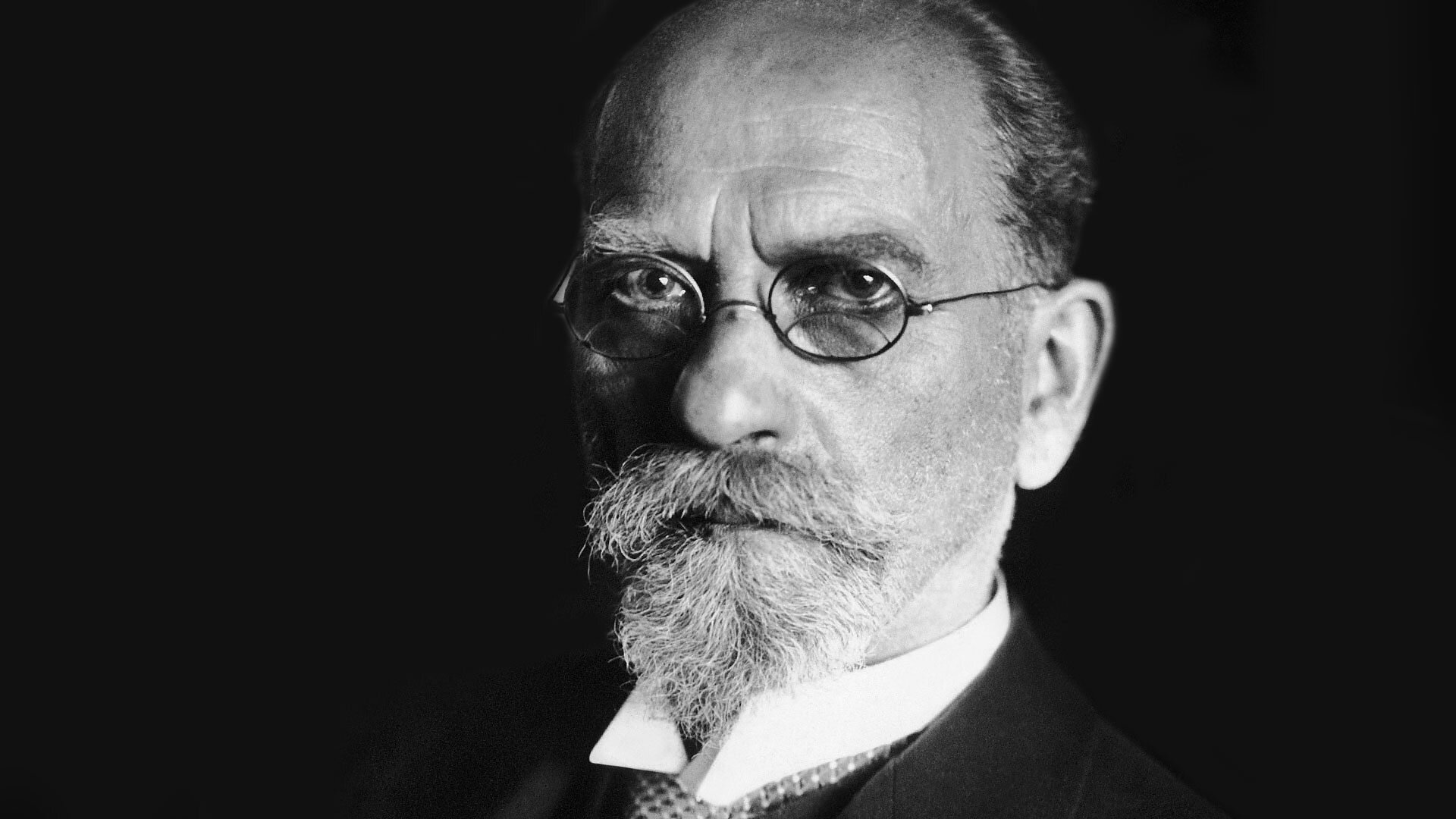

Edmund Husserl

A True Beginner

The German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) is considered the father of phenomenology, one of the most important trends in 20th-century philosophy.

Edmund Husserl was born on April 8, 1859, in Prossnitz, Moravia. After finishing his elementary education in Prossnitz, he attended schools in Vienna and Olmütz. In 1876 he entered the University of Leipzig, pursuing physics, astronomy, and mathematics. He proved to be especially gifted in mathematics, and in 1878 he moved to the University of Berlin to study with a number of the leading mathematicians of that era. He became profoundly interested in the question of the foundations of mathematical reasoning, and he took his doctoral degree in mathematics at Vienna in 1883. Thereafter, however, his interest turned increasingly to philosophy, and he followed the lectures of Franz Brentano with great interest.

Husserl began his teaching career at Halle, initially as an assistant to the distinguished psychologist Carl Stumpf. Here Husserl published his first research into the foundations of mathematics, volume 1 of his Philosophy of Arithmetic (1891). Following British empiricism, he tried to show how the foundations were to be found in acquired habits of thought. But, yielding to sharp criticisms by Gottlob Frege, he soon revised his opinions. He then pushed the question further back into the ultimate foundations of all rational thought. Gradually he became convinced that the ultimate justification of thought patterns rested in the synthetic powers of consciousness—not in mere habits of thought but rather in indispensable concepts and relations, which, as underlying all thought, were seen to be necessary. These ultimate phenomena became now the constant objects of his tireless research.

Husserl's first preparatory studies in phenomenology were published as The Logical Investigations (2 vols., 1900-1901). Called to a professorship at Göttingen (1901-1916), he continued to write extensively. Works from this period include The Idea of Phenomenology, Philosophy as a Rigorous Science, and the first part of his Ideas toward a Pure Phenomenology (1913).

In 1916 Husserl was called to Freiburg as a full professor. Here he published the second and third parts of his Ideas, together with three other long works. He retired in 1929 and, remaining in Freiburg, continued to write. From this period date the Cartesian Meditations and the Crisis of the European Sciences. In all of these works Husserl doggedly pursued his vision of a radical foundation for rational thought. His passionate dedication to clarity and fundamental insight were what most impressed his students. Never satisfied with his results, however, he referred to himself at the end of his life as "a true beginner." Husserl died at Freiburg on April 27, 1938.

To the Things Themselves

Although not the first to coin the term, it is uncontroversial to suggest that the German philosopher, Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), is the “father” of the philosophical movement known as phenomenology. Phenomenology can be roughly described as the sustained attempt to describe experiences (and the “things themselves”) without metaphysical and theoretical speculations. Husserl suggested that only by suspending or bracketing away the “natural attitude” could philosophy becomes its own distinctive and rigorous science, and he insisted that phenomenology is a science of consciousness rather than of empirical things. Indeed, in Husserl’s hands phenomenology began as a critique of both psychologism and naturalism. Naturalism is the thesis that everything belongs to the world of nature and can be studied by the methods appropriate to studying that world (that is, the methods of the hard sciences). Husserl argued that the study of consciousness must actually be very different from the study of nature. For him, phenomenology does not proceed from the collection of large amounts of data and to a general theory beyond the data itself, as in the scientific method of induction. Rather, it aims to look at particular examples without theoretical presuppositions (such as the phenomena of intentionality, of love, of two hands touching each other, and so forth), before then discerning what is essential and necessary to these experiences. Although all of the key, subsequent phenomenologists (Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Gadamer, Levinas, Derrida) have contested aspects of Husserl’s characterization of phenomenology, they have nonetheless been heavily indebted to him. As such, he is arguably one of the most important and influential philosophers of the twentieth century. The key features of his work, and his understanding of the phenomenological method, will be discussed in an upcoming weekend seminar.

See also:

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Science Direct

The Phenomenological Approach

The phenomenological approach has at least four components.

First and as stated above, phenomenologists tend to oppose naturalism. Naturalism includes behaviorism in psychology and positivism in social sciences and philosophy. The term also refers to a worldview based on the methods of the natural sciences. In contrast, phenomenologists tend to focus on the socio-historical or cultural lifeworld and to oppose all kinds of reductionism. Second, they tend to oppose speculative thinking and preoccupation with language, urging instead knowledge based on ‘intuiting’ or the ‘seeing’ of the matters themselves that thought is about. Third, they urge a technique of reflecting on processes within conscious life (or human existence) that emphasizes how such processes are directed at (or ‘intentive to’) objects and, correlatively, upon these objects as they present themselves or, in other words, as they are intended to. And fourth, phenomenologists tend to use analysis or explication as well as the seeing of the matters reflected upon to produce descriptions or interpretations both in particular and in universal or ‘eidetic’ terms. In addition, phenomenologists also tend to debate the feasibility of Husserl’s procedure of transcendental epoché or ‘bracketing’ and the project of transcendental first philosophy it serves, most phenomenology not being transcendental.

Primary Sources

Husserl: Psychological and Transcendental Phenomenology and the Confrontation with Heidegger

Introduction to Phenomenology

The Phenomenology of Perception

Secondary Sources

The Phenomenological Movement Pt. 1

The Phenomenological Movement Pt. 2

“Thus "phenomenology" means αποφαινεσθαι τα φαινομενα -- to let that which shows itself be seen from itself in the very way in which it shows itself from itself.”